Mrs. Goodwin had three children: Lily, Daniel, and the computer.

Lily was my best friend: eleven years old, like me, tall and gangly and blonde, full of sharp laughter and soft words. Her room spilled over with things each time I visited, battered Barbies and hand-me-down clothes clamoring for attention. I’d take a handful and sit with her, drowning myself in pinks and powders and shrieking laughter.

Daniel was older–fourteen, an impossible age to imagine–and as broad-shouldered and solemn as any adult. He spoke little and drifted from place to place, keeping his language quiet and close to his chest. His room was a closed door and an unknown void beyond it, which he slipped into when he needed to not exist.

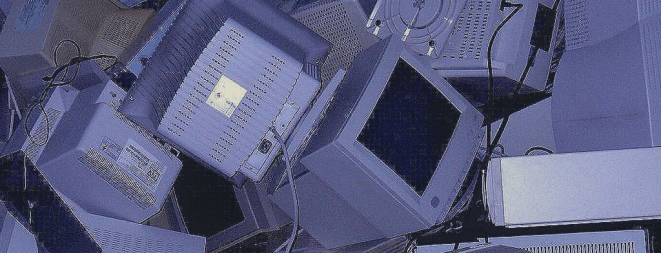

The computer was younger: one year old. It sat in a heavy beige shell, staring through a black cathode eye, and when it ran, it coughed with a sweet stench of ozone and a rush of dust. Its room was the computer room–a musty stretch of basement flooring, where every couch and box left down there to rot had been shoved aside to make room for a desk, a tattered office chair, and it.

We all loved the computer.

The computer hadn’t grown into itself yet–no touchscreens or apps–but there was an idea of what it could be. Like us, it was all awkward joints and stuttering thoughts, loud noises and fumbling language. It was, like us, still learning what it could be, and we helped it along like children do.

// Let’s grow up together, you and I.

The computer would screech when connecting online, and we’d babble back, like we were laughing together. It’d load a page and its fans would heave with effort, and then it’d finish and the fans would slow down in a puff of warm air as if it was sighing in relief. And when it went to sleep, we’d watch until its lights went out, then creep away so it could sleep in peace.

But Daniel, he was the one who first learned how to code–how to speak to the computer and have it reply. He’d stare at it through his thick glasses, and the thick cathode eye would stare back, and he’d write down a string of brackets and gibberish that the computer would turn into pictures and graphics. We watched over his shoulder as he worked, building strange worlds out of lines and measurements.

“You’re really good at this,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said, and smiled. It was the first conversation we’d ever had.

“How far does it go?” I asked Lily, zooming in and out on the fractal pattern he’d drawn. She shrugged.

“He never told it to stop, so… forever, I guess.” She trailed off. “It just goes on and on forever.”

It was then that I understood what magic was.

In school, Lily and I learned about golems–about how people long ago would trace the arcane names of God into clay to breathe life into it. If you knew the right names, we learned, you could bring anything to life: music, pictures, and the voices of people from continents away, blooming through wires and clay.

“But of course, the golems weren’t real people,” our teacher said. “They didn’t talk or think like we do. They shambled around and did tasks.”

And it seemed to me that of course they wouldn’t talk or think like we do: that their language would be mostly brackets and slashes and <image.png>, and their imaginations would be as simple yet dizzyingly infinite as a fractal drawing. Did that make them not real?

Later, at Lily and Daniel’s house, I saw their mother leaning over the counter with the phone pressed against her ear. Her fingers curled around the cable, squeezing and unsqueezing, strangling the runes flowing through it.

“I just don’t know what’s wrong with Daniel. He knows I love him, right? But it’s so hard to talk with him when he barely replies back. I’m just… exhausted.”

And I stood there, perched on the basement stairs, a lukewarm Coke in hand. She hadn’t seen me, so I crept on downwards, back to the computer desk, where the fans purred and I pressed my head to the tower’s warm side and I felt safe.

Later still, weeks on, the computer spat out a news article: a woman several miles away had killed her disabled son. He’d had a meltdown, screaming and clawing at her, and something within her snapped. She’d calmed him down and gotten him home, then fed him sleeping fills ground into his milk. Then she’d patted his hair and told him how much she loved him as he drifted to sleep like a computer winding down.

There was a picture of her, in the article. She was short and round, hunched into her oversized sweater, her hands speckled with bruises. She looked less like a mom and more like a small child, wondering how it ended up here.

After reading the article, Daniel retreated into his room. Lily and I knocked on his door, but he didn’t answer. So we camped out in front of the door, her Barbies splayed across the hallway carpet like playing cards.

“Don’t bother,” their mom said when she saw us. Her hair hung in front of her face and the edges of her sweatshirt were frayed. “He’ll come out eventually. Why don’t you find something else to do? I don’t like you all spending that much time on the computer, so maybe go outside or something.”

As Lily and I shuffled out, I saw their mom knock on Daniel’s door and say, in an exasperated voice: “I love you, Daniel.”

And I couldn’t help but wonder, if she didn’t love him retreating to his room, or his coding, or his quiet replies, what part of him did she love at all?

That evening, before heading home, I nudged the computer awake–“Hey, little buddy, time to get up”–and read the article again. There were comments on it, now, and I scrolled through them.

Sharron R., from Oregon, wrote in:

“What a tragic story! His mother must have been in so much pain. Children like that aren’t able to be reasoned with like we can. She probably did her best to help him and finally broke down.”

Carrie P., from California, added:

“Great article! As a mom, I feel nothing but heartache for that woman. If my daughter ever ended up that way, I don’t know what I would do. It would be too horrible to bear.”

Grant S., from New York, replied:

“Don’t worry. Autism that extreme only affects boys. Keep her away from vaccinations, and she’ll be fine.”

// Thank goodness.

I thought.

// I’m safe. No one can get me.

And I wondered how weird it was to feel so relieved. As if mothers were something I had to protect myself from, as if the life they’d given me could be snuffed out of me as easily as wiping an inscription off a slab of wet clay.

(Did that make me not real? I thought about sending a message to Daniel to ask, something in brackets and fractals, but I couldn’t find the words in any coding book or how-to guide I read.)

Their mom threw out the computer later that year, replacing it with a smaller, silver one. It had a thinner screen and a smaller tower, with fans that clicked instead of whirred.

Outside Daniel’s room, Lily and I watched her heft the old computer away. I stepped forward, wanting to stop her or object, but I couldn’t find the words to talk with her. All the language I knew–all the fractals and code–weren’t words she could understand.

// We were supposed to grow up together.

“Thank God,” their mom said, as she carried the new box inside. The sleeves of her sweater fell over her arms, like a small child’s. “I never understood how the old one worked. This one is better.”

She moved on to the basement to set it up. Lily–a newer version of Daniel, a better version, safe and feminine and full of shrieking, girlish words–went after her.

And me? I stayed behind, close to the door. I reached out to the knob, but stopped myself.

Underneath the door, dribbling through the crack, was a pool of wet clay, still sparking with electricity.